The Signification of Language; Privacy feat. Noah Webster

by D. Diederot

If there exists some notion of a self-styled authority of the English Language, a prideful curmudgeon reclused to his parchment and ink, it is terribly incorrect.

Noah Webster goes it solo. photo via Library of Congress.

Noah Webster was tremendously active and well-respected outside of the lexicographic niche; he joined the ranks of his father’s militia company to fight in the war of Independence; studied law at Yale University, later admitted to the bar. He frequently contributed to the Federalist papers, established New York’s first daily newspaper, The American Minerva, and pioneered a national lecture circuit with public calls for education reform, social welfare improvement, and opposition to slavery. Well connected with the first leaders of America, he wrote and shared a large number of political pamphlets, drafted policy proposals, and was instrumental to the creation, and later revision, of national copyright law.

All this, and the name Webster is inescapably acquiescent to that of Merriam, by a single, simple, tragic hyphen. Noah’s uncompromising pursuit of the genuine orthography of the English language ratified the compilation of a dictionary unlike any prior. Among the first generations of Americans, his early years were marked by injustices imposed by the Crown, and he put aside his studies at Yale University to fight in the War of Independence.

Noah Webster’s earliest success as a writer was found among the little baby American audience. A Grammatical Institute of English Language, a basic school textbook written to replace the outdated, English-centric “Guide to the English Tongue”. His the three-part series was taught in school houses throughout the thirteen states, and while the royalty was less than one cent per copy, the income from the textbooks were enough to sustain himself and family for the next few decades, as he embarked on his Great Task to compile the first American English dictionary for his fellow citizens.

An early compilation of the English Language, to which he refers as A Compend, was a humble dictionary, as its title does imply, but it also served as a sort of orthographic down-payment, a prototype of work to come, in which he lays forth his motivations for the undertaking;

“A thorough conviction of the necessity and importance… has determined me to make one effort to dissolve the charm of veneration for foreign authorities which fascinates the mind of men in this country, and holds them in the chains of illusion.”

By his own account, after writing through two letters of the alphabet, Noah was embarrassed at every step, by his lack of knowledge of the origin of words, and resolved to set aside his writing completely in order to “obtain a more correct knowledge” of about twenty languages (!). After only three years of this new direction, Noah describes having to change his approach again, to “unlearn a great deal” of his years in study so to properly examine the rudiments of a branch or erudition. Ten years he spent at this granular stage. Ten!

The depths of his diligence resulted in a dictionary unlike any prior; the structure of each entry is a time-capsule, retracing a word to its origin not because doing so was the standard, but because revealing the genuine principles of a word was paramount. Does this sound like a man indulging over his obsessions? Maybe. Yes. But do see for yourself before too harsh a judgement;

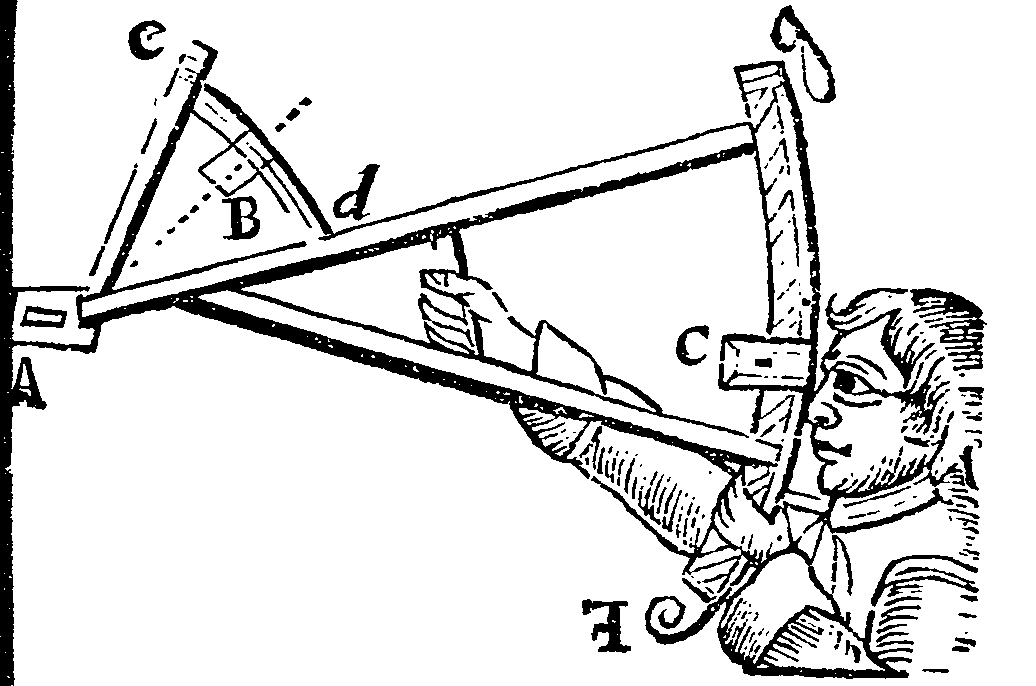

Private, a.

From Latin privatus, from privo: to bereave. Properly, to strip or separate. Privus: singular, several, peculiar to one’s self, that is, separate. Italian, privare; Spanish, privar; French, priver: to deprive. Privo is probably from the root bereave; in Saxon-English, bereafian or gereafian, from refian: to strip, to spoil. From Latin ripio, diripio, eripio; privo for perivo or berivo. Welsh, rhaib: a snatching, from rheibiaw: to snatch.

Damn, right? 1828 finally saw the publication of the above inside An American Dictionary of the English Language, followed by a significant two-volume expansion in 1841. Little more than two years later, Noah died.

Financially, it was a disaster. In today’s purchase power, a single copy is estimated to cost between $400 – $500, and inconceivable price for his earlier readers of public schools and their students. Out of necessity, his (real) heirs resolved to selling the remaining prints, eventually finding a buyer in the firm of J.S. & C. Adams. But they too found the volumes burdensome to sell, and plainly wanted them off their hands.

Hello, Merriam.

Booksellers and professionals in print, bothers Charles and George Merriam saw the opportunity. The Adams firm happily accepted the purchase offer, and along with the physical copies, gave the G. & C. Merriam Company the rights of revision, rights of publication, and exclusive trademark rights to the Webster name.

For the next few decades, the Merriam formatted, re-formatted, and re-re-formatted Webster’s American Dictionary into a single volume publication; their cost-cutting strategy of manufacturing allowed them to sell a dictionary at such a reduced price that, for the first time, the common man could afford its purchase.

The company thrived, without even touching Noah’s original writing, and despite having the rights to do so; a second edition included rich illustrations, a third saw the addition of new sections like biography and geography. The first actual changes would not appear until the 60s. Yes, you read that correctly.

At this point, The G & C Merriam Company had amassed an impressive reputation as lexicographical publishers, and dominance of a meagre market of English Language reference books. By the end of the century, much of the public associated “Webster” with “dictionary”.

However. Honeymoon is over. The copyrights to all of Noah Webster’s work had expired. The entirety of G. & C. Merriam Company’s best-selling publication, the 1841 edition of American Dictionary, had entered public domain, along with the Webster name. Any publisher, if so inclined, could publish, verbatim, the complete 1841 edition, entitle it “Webster’s Dictionary”, and enjoy full compliance of copyright and trademark law. The same laws, as it were, that Noah Webster brought successfully before Congress.

Deary-me, Merriam.

Other than reputation— built upon a public-domain term, no less— the G. & C. Merriam Company had little to differentiate itself from a rapidly growing competitive market.

So began an aggressive legal campaign.

Case after case, the Courts ruled in favour of the public’s interest. Despite, the strategy continued at full force well into the 20th century. If anything, Merriam concluded that, after roughly one hundred and thirty (!) years after first gaining the rights of its use, the company changed their name to “Merriam-Webster”.

Perhaps the final blow was imparted by the decision in G. & C. Merriam Co. v. Webster Dictionary Co., two years before the name change. In the court’s memorandum, the court noted that;

Merriam et. al. v. Texas Siftings Pub. Co., 1892

G. & C. Merriam Co. v. Saalfield, 1911

G. & C. Merriam Co. v. United Dictionary Co., 1905

Ogilvie v. G. & C. Merriam Co,. 1907

G. & C. Merriam Co. v. Straus, 1904

G. & C. Merriam Co. v. Syndicate Publishing Co., 1915

“plaintiff does not have the exclusive right to refer to its product as `Webster Dictionary.’ (citing G. C. Merriam Company v. Syndicate Publishing Co.)”, and that “[w]hile it may be a considerable overstatement to describe the defendant’s dictionary as world-famous, these words do not suggest that the book being sold is the plaintiff’s dictionary.”

While claims of unfair competition and demands of injunctive relief billowed throughout the Courts, Merriam published their most transformative edition of American Dictionary, “completely revised in all departments”. Examining Noah Webster’s original American Dictionary directly against Merriam’s overhauled Webster’s New International Dictionary of the English Language, published nearly a century later, raises the question of integrity in private interest. It’s your call.

An American Dictionary of the

English Language

Noah Webster, L.L. D, published by S. Converse, New York.

1828

Webster’s New International Dictionary of the English Language

published by G & C Merriam Company, Springfield, M.A.

1909

Pri’vacy, n.

[from private.]

A state of being in retirement from the company or observation of others; secrecy.

Pri’va-cy, n.

n., pl. -CIES. [See PRIVATE.]

State of being in retirement from the company or observation of others; seclusion.

2.

A place of seclusion from company or observation; retreat; solitude; retirement.

Her sacred privacies all open lie. Rowe.

2.

A place of seclusion from company or observation; retreat; solitude; retirement.

Her sacred privacies all open lie. Rowe.

3.

Privity. [Not used.] [See PRIVITY.] Arbuthnot.

3.

Concealment of what is said or done; secrecy. Shak.

4.

Taciturnity. [Not used.] Ainsworth.

4.

A private, personal, or secret matter. Fuller.

5.

Secrecy; concealment of what is said or done.

5.

= PRIVITY. Obs. Arbuthnot.

Priv’ity, n.

[Fr. privauté. See PRIVATE and PRIVY.]

Privacy; secrecy; confidence.

I will to you, in privity, discover the drift of my purpose. [Little used.] Spenser.

Priv’i-ty, n.

[pl. -TIES. ME. priveté, OF. priveté. See PRIVY.]

Privacy; secrecy; confidence.

I will to you, in privity, discover.. my purpose. Spenser.

2.

Private knowledge; joint knowledge with another of a private concern, which is often supposed to imply consent or concurrence.

All the doors were laid open for his departure, not without the privacy of the prince of Orange. Swift.

But it is usual to say, “a thing is done with his privity and consent;” in which phrase, privity signifies merely private knowledge.

2.

Private knowledge; joint knowledge with another of a private concern; cognizance implying concurrence.

All the doors were laid open for his departure, not without the privacy of the prince of Orange. Swift.

3.

Privities, in the plural, secret parts; the parts which modesty requires to be concealed.

3.

Privacy of life or condition; seclusion. Obs.

4.

A private matter; a secret. Obs. Chaucer.

5.

Intimate relations or connection. Obs. Spenser.

6.

pl. The genitals; the privates. Obs. or R.

7.

Law. A connection, or bond of union, between parties, as to some particular transaction; mutual or successive relationship to the same rights of property; the relationship between privies.

Priv’y, a.

[Fr. privé,; L. privus. See PRIVATE.]

Private; pertaining to some person exclusively; assigned to private uses; not public; as, the privy purse; the privy coffer of a king. Blackstone.

Priv’y, a.

[F. privé, fr, L. privatus. See PRIVATE.]

Of or pertaining to some person exclusively; assigned to private uses; not public; private; as, the privy purse.

2.

Secret: clandestine; not open or public; as a privy attempt to kill one.

2.

Secret; clandestine; also, hidden; not manifest; as, privy defects. Obs or R. “A privy thief.” Chaucer.

A privy thief. Chaucer.

3.

Private; appropriated to retirement; not shown; not open for the admission of company; as a privy chamber. Ezek. xxi.

3.

Private; secluded. “Privy chambers.” Ezek. xxi 14.

4.

Privately knowing; admitted to the participation of knowledge with another of a secret transaction.

He would rather lose half his kingdom than be privy to such a secret. Swift.

Myself am one made privy to the plot. Shak.

His wife also being privy to it. Acts v.

4.

Admitted to knowledge of a secret transaction; secretly cognizant; privately knowing.

His wife also being privy to it. Acts v.2.

5.

Admitted to secrets of state. The privy council of a king consists of a number of distinguished persons selected by him advise him in the admin of the government. Blackstone.

A privy verdict, is one given to the judge out of court, which is of no force unless afterward affirmed by a public verdict in court. Blackstone.

5.

Intimate; in close relations. Obs.

Priv’y, n.

[Law.]

Priv’y, n.

[pl. PRIVIES.]

1.

In law, a partaker; a person having an interest in any action or thing; as a privy in blood. Privies are of four kinds; privies in blood, as the heir to his father; privies in representation as executors and administrators to the deceased; privies in estate, as he in reversion and he in remainder; donor and done; lesson and lessee; privy in tenure, as the lord in escheat. Encyc.

1.

Any of those persons having mutual or successive relationship to the same right of property; a person having an interest in any action or thing, esp. one having an interest derived from a contract or conveyance to which he is not himself a party; —usually distinguished from party. Privies are usually classified as: privies in blood, as heir and ancestor; privies in estate, as donor and donee, lessor and lessee; privies in representation, as executor or administrator and the deceased; privies in law, as where one takes property from another by escheat.

2.

A necessary house.

Privy chamber, in Great Britain, the private apartment in a royal residence or mansion. Gentlemen of the privy chamber are servants to the king, who are to wait and attend on him and the queen at court, in their diversions, &c. They are forty eight in number, under the lord chamberlain. Encyc.

2.

A necessary; a backhouse.

3.

A close or intimate friend. Obs.

Pri’vate, a.

[L. privatus, from privo, to bereave, properly to strip or separate; privus, singular, several, peculiar to one’s self, that is, separate; It. privare, Sp. privar, Fr. priver, to deprive.

Privo is probably from the root bereave, Sax. bereafian or gereafian, from refian, to strip, to spoil. L. rapio, diripio, eripio, privo for perivo or berivo; W. rhaib, a snatching; rheibiaw, to snatch. See RIP, REAP, and STRIP.]

Pri’vate, a.

[L. privatus apart from the state, peculiar to an individual, private, properly p.p. of privare to bereave, deprive, originally, to separate, fr. privus single, private, perhaps originally, put forward (hence alone, single) and akin to prae before. See PRIOR, a.; cf. DEPRIVE, PRIVY, a.]

1.

Properly, separate; unconnected with others; hence, peculiar to one’s self; belonging to or concerning an individual only; as a man’s private opinion, business or concerns; private property; the king’s private purse; a man’s private expenses. Charge the money to my private account in the company’s books.

1.

Belonging to, or concerning, an individual person, company, or interest; peculiar to one’s self; unconnected with others; personal; one’s own; not public; not general; separate; as, a man’s private opinion; private property; a private purse; private expenses or interests ; a private secretary; a private wrong.

2.

Peculiar to a number in a joint concern, to a company or body politic; as the private interest of a family, of a company or of a state; opposed to public, or to the general interest of nations.

2.

Not invested with, or engaged in, public office or employment; not public in character or nature; as, a private citizen, private life, private schools.

A private person may arrest a felon. Blackstone.

3.

Sequestered from company or observation; secret; secluded; as a private cell; a private room or apartment; private prayer.

3.

A close or intimate friend. Obs.

4.

Not publicly known; not open; as a private negotiation.

4.

Not publicly known; not open; secret; as, a private negotiation; a private understanding.

5.

Not invested with public office or employment; as a private man or citizen, private life. Shak.

A private person may arrest a felon. Blackstone.

5.

Having secret or private knowledge; privy. Obs.

6.

Individual, personal; in contradistinction from public or national; as private interest.

Private way, in law, is a way or passage in which a man has an interest and right, though ground may belong to another person. In common language, a private way may be a secret way, one not known or public.

A private act, or statute, is one which operates on an individual or company only; opposed to general law, which operates on the whole community.

A private nusance or wrong, is one which affects an individual. Blackstone.

In private, secretly; not openly or publicly. Scripture.

6.

Maintaining secrecy; uncommunicative; as, to be private in carrying out instructions. Obs. or R.

“Massively expanded; thoroughly revised!”

Really?

If the durability of the English Language is indeed as resilient as our examination gives evidence to, and the necessity for change is but a post-revolutionist ideology briefly championed by a radical philologist, then no further complication will greatly be found as we put what we have learned into practice.

As one can see, the definition of privacy today, over a century later (!), is again, little changed.

Privacy, noun.

plural privacies

1.

a: The quality or state of being apart from company or observation: SECLUSION

b: freedom from unauthorized intrusion

2.

a: SECRECY

b: a private matter: SECRET

3.

a place of seclusion.

Enough. Moving on.

Hypothetically, we are reading a Paefoubel Policy— but pardon, what is the meaning of “Paefoubel”?. We consult our New International Dictionary, Massively Expanded and Thoroughly Revised. We learn that “Paefoubel” is, in fact, the Modern Etymology of [PRIVACY]. We return to the document in question— the Privacy Policy provided by Merriam-Webster— which reads;

“Your state of being in retirement from the company or observation of others is important to us.”

“We understand that you are aware of and care about your private, personal, or secret matter rights, and we take that seriously.”

“This Seclusion Policy sets forth your solitude rights and applies to the personal data we may collect.”

“[Our partners] may use our first-party cookie on your browser to match your shared information to their marketing databases in order to provide back a pseudonymous intimate-centric identifier for our use in real time bidding in digital advertising.”

“To respect yours and your child’s cognizance implying concurrence, [our third-party partner] collects the minimum amount of information.”

There are two points abundantly clear from this laughable exercise.

First, if we are to uphold that a dictionary, particularly Noah’s dictionary, is meant to show how a word be properly used, and has, historically, been used, using “privacy” in this context fails. It is too far removed from any of its prior use that we’re given an incoherent policy

Second, you might be thinking, “a dictionary is not a thesaurus, to use it as such will not surprisingly be ineffective. While this is true, “privacy” is so problematic that even using a thesaurus fails to provide understanding. From Merriam-Webster’s thesaurus, the first synonyms;

“insulation, isolation, secludedness, seclusion.” Sound familiar?

It should by now be blindingly clear that “privacy” is a failure of a term when hijacked for the digital context. The American English language evolved from British English as a result of its use in an entirely new context; a new nation, America. It is not inconceivable that the creation of the digital context require another lineage of evolution. While this author hesitates to call our new domain as “digital English”, because it sounds ridiculous. But is it better than a failure to reconsider the useless encumbrances we are creating, this lazy and embarassing standard of negligently applying tangentially similar words? Your call.

The English language is complicated AF. It is rich in tenses, beyond any other language in Europe. Grammar and pronunciation are full of obtuse exceptions. Some words do not neatly fall into any category or function already devised. This ambiguity, coupled with rapid technological advancements which require the creation of entirely new terms, could not be a more bitingly obvious reason to address the matter. In Noah’s parallel to our own, he notes that the tactics used in attempt to remedy this, much like our modern strategy of copy/paste,

“serve only to obscure and embarrass the subject by substituting new arrangements and new terms, which are as incorrect as the old ones, and less intelligible.”

If you have any questions or concerns, please send an email to:

privately-knowing@merriam-webster.com.